relation / manipulation / mutation

ABOUT THE PIECE:

The piece is inspired by Michael Pollan’s book The Botany of Desire – a plant’s-eye view of the world.

The recorded voice reads excerpts of his book and theory on how plants are superior to human beings.

The piece circles around mutation through slow natural selection, and how we as human beings think we control plants, but that it might be completely opposite.

“…it makes just as much sense to think of agriculture as something the grasses did to people as a way to conquer the trees.”

Michael Pollan has allowed the piece to be created in 2020, and has seen and applauded the final result in 2025.

ARTISTIC TEAM:

Text by Michael Pollan in collaboration with Lil Lacy

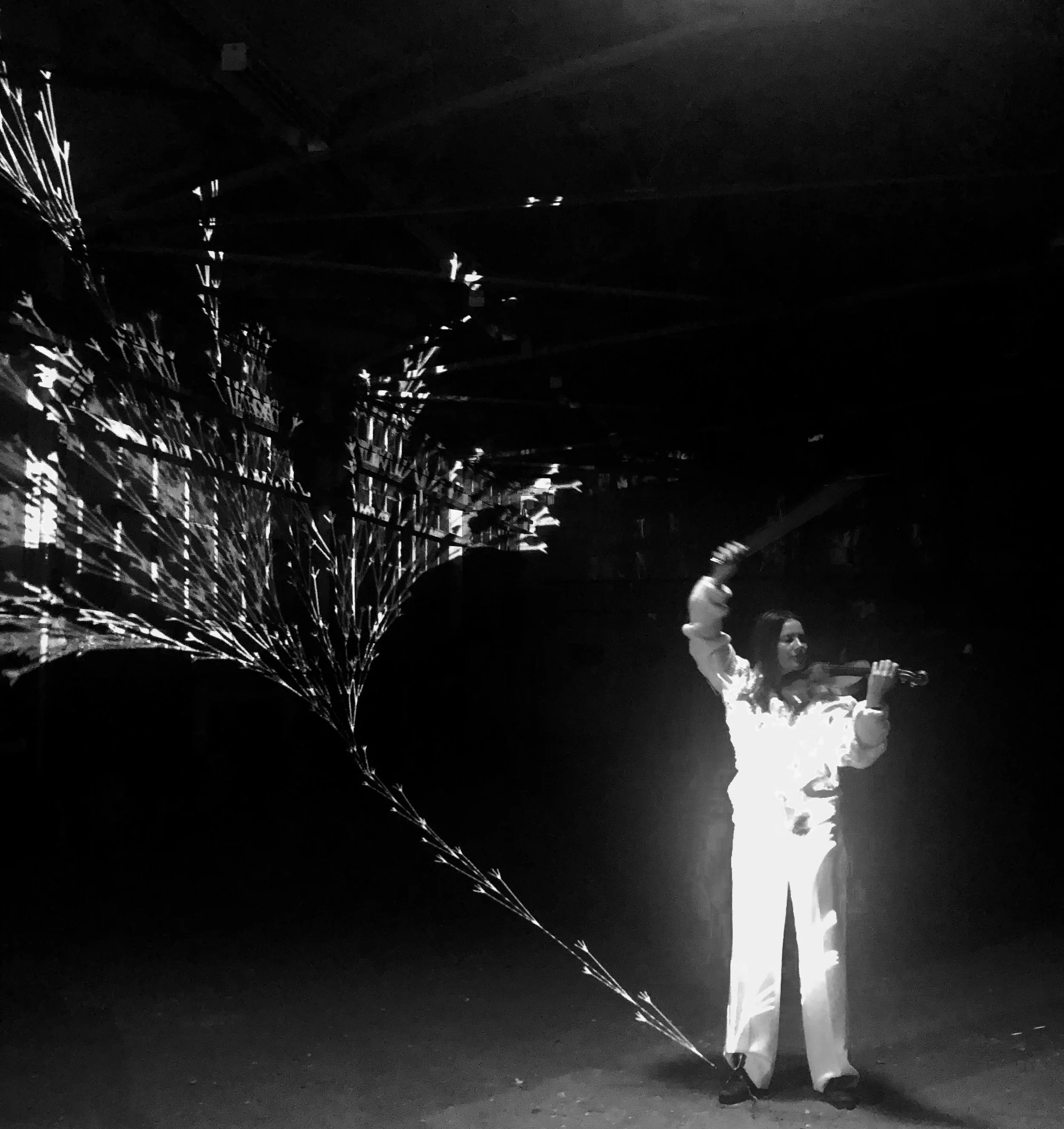

Music performed by Lil Lacy (spoken voice) and Anna Jalving (violin and performance)

Music composed by Lil Lacy

Knit by Maibritt Marjunardóttir

Light scenography by Vertigo; Frederik Svanholm, Amalie Solander, Jeppe Deibjerg, Mikkel Meyer, Vibeke Bertelsen

Acoustic sound recording and mix by Preben Iwan

Technical recording assistance by Stefanus Søe Iwan

Filmed by Philip Engsig

Editing and color grading by Kristopher Paterson

Thank you to Kulturværftet in Elsinore, Denmark and all that have been involved in this production.

SECRET LINK TO THE COMPLETE PIECE (sound in stereo):

WORLD PREMIERE:

Has not had a world premiere yet.

CAST & CREW:

1 composer, 1 sound technician and 2 visual artists are involved in the set-up of the complete installation, besides the inhouse crew.

SPACE:

A black box-style space where the audience can freely enter and exit as they please.

The sound and light from other spaces will preferably not interfere too much with the experience in the space.

DURATION: 17:15 min. (can be looped)

CO-PRODUCTION:

Vertigo

Lil Lacy Music

SUPPORTED BY:

The Augustinus Foundation

TECHNICAL DETAILS:

Video

The video content is formatted in standard 4K at a 16:9 aspect ratio, ensuring compatibility with most standard setups.

For optimal staging and audience experience, we recommend the following:

Screen Specifications:

A floor-to-ceiling screen is preferred to create a seamless and immersive experience, as the film primarily features full-frame visuals. The screen will act as an extension of the room, enhancing the integration of the film with the space.

If the ceiling height is 260cm, the screen width should be 462cm to maintain proper proportions.

The screen can be either an LED display or a projection screen, depending on the venue's capabilities.

Audio

2 delivery formats are available for relation / manipulation / mutation

DCP for Cinemas:

Video format ; 4K - 16:9

Audio format ; DCP containing Dolby Digital Atmos Audio 7.1.4 (WAV files/MXF wrapper at 24-bit 96kHz)QuickTime movie : (for consumer and professional installation playback)

H.264 video with Dolby Atmos Audio 7.1.4 - ( 24-bit 96kHz) - (at least Dolby Atmos Audio 5.1 format should be available for playback)

THE COMPLETE TEXT

Plants are so unlike people that it’s very difficult for us to appreciate fully their complexity and sophistication. Yet plants have been evolving for much, much longer than we have; have been inventing new strategies for survival and perfecting their designs for so long that to say that one of us is the more “advanced” really depends on how you define that term; on what “advances” you value.

Naturally we value abilities such as consciousness, toolmaking and language, if only because these have been the destinations of our own evolutionary journey thus far. Plants have traveled all that distance and then some – they have just traveled in a different direction.

Plants are nature’s alchemists, experts at transforming water, soil, and sunlight into an array of precious substances, many of them beyond the ability of human beings to conceive, much less manufacture. While we were nailing down consciousness and learning to walk on two feet, they were, by the same process of natural selection, inventing photosynthesis (the astonishing trick of converting sunlight into food) and perfecting organic chemistry. As it turns out, many of the plant’s discoveries in chemistry and physics have served us well. From plants come chemical compounds that nourish, heal, poison and delight the senses, others that rouse, put to sleep and intoxicate, and a few with the astounding power to alter consciousness – even to plant dreams in the brains of awake humans.

Why would they go to all this trouble? Why should plants bother to devise the recipes for so many complex molecules and then expend the energy needed to manufacture them?

One important reason is defense.

A great many of the chemical’s plants produce are designed, by natural selection, to compel other creatures to leave them alone: deadly poisons, foul flavors, toxins to confound the minds of predators. But many other of the substances plants make have exactly the opposite effect, drawing other creatures to them by stirring and gratifying their desires.

The same great existential fact of plant life explains why plants make chemicals to both repel and attract other species; immobility.

The one thing plants can’t do is move, or, to be more precise, locomote.

Plants can’t escape the creatures that prey on them; they also can’t change location or extend their range without help.

And so, about a hundred million years ago plants stumbled on a way – actually a few thousand different ways – of getting animals, wind or water to carry them, and their genes here and there. This was the evolutionary watershed associated with the advent of the angiosperms, an extraordinary new class of plants that made showy flowers and formed large fruits with seeds that other species were induced to disseminate, to spread widely sowing their seeds.

Plants began evolving burrs that attach to animal fur like Velcro, flowers that seduce bees in order to powder their thighs with pollen, and acorns that squirrels obligingly taxi from one forest to another, bury, and then, just often enough, forget to eat.

Even evolution evolves. About ten thousand years ago the world witnessed a second flowering of plant diversity that we could come to call somewhat self-centeredly, “the invention of agriculture”.

A group of angiosperms, flowering plants, refines their basic put-the-animals-to-work strategy to take advantage of one particular animal that had developed not only to move freely around the earth, but to think and trade complicated thoughts. These plants hit a remarkably clever strategy: getting us to move and think for them. Now came edible grasses (such as wheat and corn) that incited humans to cut down vast forests to make more room for them; flowers whose beauty would transfix whole cultures; plants so compelling and useful and tasty they would inspire human beings to seed, transport, extol, and even write books, poems and songs about them.

Am I hereby suggesting that plants made me do it? Only in the sense that the flower “makes” the bee pay it a visit.

Evolution doesn’t depend on will or intention to work; it is, almost by definition, an unconscious, unwilled process.

All it requires are beings compelled, as all plants and animals are, to make more of themselves by whatever means trial and error present. Sometimes an adaptive trait is so clever it appears purposeful: the ant that “cultivates” its own gardens of edible fungus, for instance, or the pitcher plant that “convinces” a fly it’s a piece of rotting meat. But such traits are clever only in retrospect. Design in nature is but a concatenation of accidents, a series of interconnected or interdependent events, trials and errors, culled by natural selection until the result is so beautiful or effective as to seem a miracle of purpose.

By the same token, we’re prone to overestimate our own agency in nature. Many of the activities humans like to think they undertake for their own good purposes – inventing agriculture, outlawing certain plants, writing books, words and music in praise of others – are mere contingencies as far as nature is concerned.

Our desires are simply more grist for evolution’s mill, no different from a change in the weather: a peril for some species, an opportunity for others.

Our grammar might teach us to divide the world into active subjects and passive objects, but in coevolutionary relationship every subject is also an object, every object a subject.

That’s why it makes just as much sense to think of agriculture as something the grasses did to people as a way to conquer the trees.